Here is an off-the-cuff list of my thirty nine "favorite" movies at present. Check out my "this is a gut feeling thing, not a critically thought-out thing" caveat the first time I did this, and see also my lists from August 2014 and November 2015 if you give a crap.

There's a new rule this time: to put a film on this list, I have to have watched it within the last two years.

Here goes:

Gas Food Lodging (1992)

Lovely and Amazing (2001)

Alien (1979)

The Terminator (1984)

Shadow of a Doubt (1943)

Blade Runner (1982)

Peeping Tom (1960)

The TV Set (2006)

Duel (1971)

Assault on Precinct 13 (1976)

Escape from New York (1981)

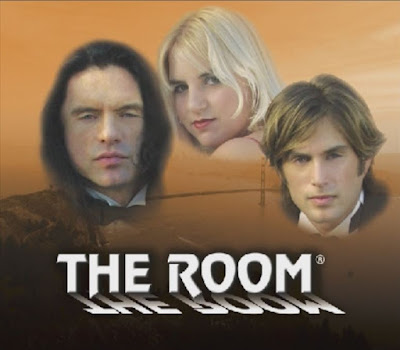

The Room (2003)

Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986)

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974)

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

The Brood (1979)

Heat (1995)

12 Angry Men (1957)

Shampoo (1975)

Nashville (1975)

Paradise Lost 2: Revelations (2000)

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Barry Lyndon (1975)

The Shining (1980)

Cure (1997)

The Witch (2015)

Das Boot (1981)

Leviathan (2015)

Far From the Madding Crowd (2015)

Throne of Blood (1957)

The Third Man (1949)

Memories of Murder (2003)

Prometheus (2012)

Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

Fargo (1996)

A Serious Man (2009)

Terri (2011)

Nosferatu (1979)

The Thin Blue Line (1988)

Some comments:

The Third Man is on the list this time because it is the best fuckin' 1940s film noir there is (and if not this, then Double Indemnity). I have always loved The Third Man. It has my favorite tone of any film noir or practically any film, absurdly whimsical yet pervasively melancholic -- and deadly serious when it needs to be. Its use of setting is unparalleled. It has one of the best soundtracks ever. It features one of Orson Welles' best onscreen performances. It only gets better with time. Everything about it is beautiful and awesome.

Joseph Cotten and Alida Valli in Carol Reed's noir masterpiece The Third Man.

The Brood is here because it's the most recent David Cronenberg film I've laid eyes on, and anything that guy does, up to and including Eastern Promises (2007), pretty much mesmerizes me. I would normally place Videodrome as my all-out favorite Cronenberg outing, but I saw The Brood at the Dryden last year and it really blew me away. So creepy!

I substituted Das Boot for Fellini's La Dolce Vita (1960), since I realized it's probably been over two years since I saw the latter. I saw Das Boot more recently and Wolfgang Petersen's anti-war masterpiece, a perennial favorite, has been on my mind a lot lately.

Similarly, I traded Stanley Kubrick's Eyes Wide Shut for Kiyoshi Kurosawa's Cure, for the same reason -- I haven't seen Eyes recently, but I watched Cure earlier this year.

The most important new addition is Tommy Wiseau's schlock masterpiece The Room, which I had the good fortune to re-watch with an exuberant group of friends last weekend. I made an important plot-related realization during this latest viewing: the drug dealer Chris-R (Dan Janjigian) is essentially there to deliver the gun to Johnny. The gun Johnny confiscates from Chris-R during the rooftop scene is the same one he uses to rather dramatic effect in the film's final sequence.

Which is to say, The Room's "what kind of drugs?" subplot is in the film not just at random, but exists to serve a higher plot function. Sure, Chris-R is apparently sent to jail (as Denny claims during his rooftop confrontation with Lisa and Claudette) without the San Francisco Police ever investigating Denny's involvement in his drug dealings. Nor do the cops ever come looking for that gun. But these "plot holes" are rather minor when compared to the film's need to explain how the naive Johnny gets access to a handgun, wouldn't you say?

A few movies that should be on the list but aren't because I stopped at thirty nine this time include Vampyr (1932), King Kong (1933), The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997), and probably Crimson Peak (2015).

"Why is this happening to me?"