Spring Breakers, the most artful, sublime, and culturally savvy film I saw this year.

I prefer to call this end of the year reflection a "roundup" because I am somewhat opposed to the idea of "best of" lists or even the idea of "best" when applied to works of entertainment or art in the first place. These things are so damn subjective that, although I am surely subject to my own outbursts of praising or condemning hyperbole when discussing cinema, I do not wish to convey that I place much faith in rankings of "best films" whether such lists are composed by me or by others.

All that said, I understand the compulsion to collect one's thoughts at the end of a year and to make some kind of temporarily definitive statement about the highlights of one's moviegoing experiences in the 365 days just passed. So with that in mind, and in no particular order, here are some of the most memorable films and filmgoing experiences I've had in 2013.

Chiwetel Ejiofor as Solomon Northup in Steve McQueen's powerful anti-slavery film

12 Years a Slave.

The most impactful films of 2013 for me include 12 Years a Slave, Only God Forgives, Enough Said, Spring Breakers, Blackfish, and The Heat. Please factor into this that I have not yet seen other promising 2013 releases such as Inside Llewyn Davis, Nebraska, Frances Ha, Before Midnight, or practically any of the films on this list (let alone this one).

I have discussed Only God Forgives and Enough Said elsewhere, and am still working on a stand-alone review of the Steve McQueen masterpiece 12 Years a Slave, but I will say a few words about those other three films now.

While 12 Years is probably the most historically "important" film listed above, and the most emotionally wrenching for sure, I have to choose Harmony Korine's satirical, postmodern masterpiece Spring Breakers as my personal favorite this year. As Tom Carson so eloquently puts it in his assessment of the film,

While 12 Years is probably the most historically "important" film listed above, and the most emotionally wrenching for sure, I have to choose Harmony Korine's satirical, postmodern masterpiece Spring Breakers as my personal favorite this year. As Tom Carson so eloquently puts it in his assessment of the film,People have debated whether Spring Breakers sends up the prurient appeal of exploitation movies or is just prurient, but that's missing the point: both are true. [. . .] What's most startling about the movie is how breezily but bluntly it lays bare white America's "I wanna be black" race fantasies. [. . .] In this movie Korine is as sharp as any director ever has been about the sexual and racial pathologies that underlie so many forms of American craziness.Indeed. It is a postmodern masterwork that accurately depicts where we are right now. It is also, at the same time, a remarkable and very sensitively crafted teenaged coming-of-age story that is, if not explicitly feminist, at least female-positive.* That is quite an achievement. Add to this Korine's remarkable talent for capturing indelibly beautiful (if sometimes disturbing) visual images, a talent which, if anything, has matured since his earlier works Gummo (1997), Julien Donkey-Boy (1999), and Mister Lonely (2007), and you have in Spring Breakers a stunning art film cum-social critique that every thinking American should see.

Blackfish, by contrast, is a well-produced but relatively straightforward documentary, more noteworthy for its heartbreaking subject matter than its formal innovation. Taking as its focus a series of (mostly covered up) lethal attacks upon various SeaWorld trainers over the decades, Blackfish documents the irreparable psychological damage done to orca ("killer whales") who are captured and held in captivity as marine zoos and theme parks. As this article suggests, watching the film may sour you on taking a trip to SeaWorld but it will touch your conscience and your emotions and will raise your awareness about the human species' ethical obligation to our oceangoing mammalian brethren. A chilling, emotionally compelling must-see.

One of the final shots of Blackfish, depicting a pod of orca

where they belong: in the wild.

where they belong: in the wild.

The Heat is the laugh-out-loud funniest film I've seen since at least Bridesmaids (2011) and possibly even Superbad (2007). Melissa McCarthy and Sandra Bullock, the well-paired stars of this straight-ahead buddy comedy, have excellent onscreen chemistry; The Heat is hilariously funny throughout yet integrates a few touching moments between the two leads that do not come off as too schmaltzy or sentimental. The writing and direction are top-notch. I wish they'd given Jane Curtin a more substantive role and more screen time as McCarthy's hard-edged mother. But ultimately I highly recommend The Heat if you want to laugh. I hope that the runaway success of the film leads to more consistent production of female-led comedies in Hollywood going forward.

Pre-2013 films I finally saw and am so happy I did include Take This Waltz (2011), Marie Antoinette (2006), Adam's Apples (2005), We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011), Chasing Ice (2012), Shallow Grave (1994), and Berberian Sound Studio (2012).

I have reviewed Sarah Polley's superb relationship drama Take This Waltz elsewhere, and plan to discuss Marie Antoinette in a separate post on Sofia Coppola and Adam's Apples in a post on Mads Mikkelsen.

Scottish director Lynne Ramsay's We Need to Talk About Kevin is probably the single most disturbing film I saw this year, about a mother coming to terms with the fact that her son may be a sociopath. As a thriller/family melodrama, the film is both a real nail-biter and a poignantly beautiful paean to the struggles of motherhood -- Tilda Swinton, always an actress to watch out for, gives a harrowingly raw and ultimately quite tender performance as Kevin's seemingly emotionally distant mother. I just cannot recommend this film highly enough; it is a must-see.

Ezra Miller as Kevin in Lynne Ramsay's harrowing family drama

We Need To Talk About Kevin.

Chasing Ice is a beautifully shot documentary about environmental photographer James Balog's decade-long quest to document the retreat of the world's glaciers as a result of global climate change. His time-lapse photography, shown in the last twenty minutes of the documentary, is so sublimely horrifying that I think every citizen of Earth should see it. However, equally compelling and worth seeing is the whole lead-up to that jaw-dropping footage, in which we see what a painstaking process it was for Balog to capture it in the first place.

Of Shallow Grave and Berberian Sound Studio I have little to say other than they are both excellent, even exceptional genre films: Grave a darkly comic suspense thriller / neo-noir about three roommates who plot and execute a murder together, and Berberian a horror film / art film that is also a loving homage to the Italian giallo horror film tradition -- with a twist. I recommend Danny Boyle's witty and accessible Shallow Grave to anyone; Berberian Sound Studio is probably best appreciated by folks with at least a passing knowledge of Italian horror (see at least Suspiria first) and an openness to films that end ambiguously.

Noteworthy 1960s and 1970s films I saw for the first time this year include The Yakuza (1974), Blue Collar (1978), When Eight Bells Toll (1971), Juggernaut (1974), The Wild Geese (1978), and L'Avventura (1960).

I saw The Yakuza (1974) and Blue Collar (1978) when I was on a brief Paul Schrader jag this summer -- he scripted both films and directed the second. Both are superb if you enjoy 1970s Hollywood cinema. For me, The Yakuza was the real standout, bringing an aging Robert Mitchum back for a revisionist noir set in Japan. While a bit Orientalist, the film is extremely well made and yields many delights for fans of noir-ish thrillers. Blue Collar is actually more hard-hitting thematically, dealing as it does with the (corrupt, racist) politics of the automobile labor unions, and it features killer performances by Richard Pryor, Harvey Keitel, and Yaphet Kotto.

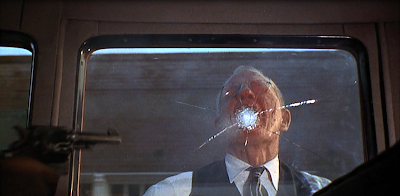

Anthony Hopkins in the delightful, James Bond-esque

espionage thriller When Eight Bells Toll.

When Eight Bells Toll is one of my most unexpected discoveries this year -- I found it when perusing Netflix streaming offerings looking for British thrillers. Bells is essentially a James Bond film without James Bond in it. Anthony Hopkins plays an experienced secret agent on a dangerous mission in northern England; many plot points remind me of From Russia With Love and Dr. No. If you are a fan of the early Bonds and/or Hopkins, When Eight Bells Toll is not to be missed!

Juggernaut and The Wild Geese were films I found during my summer quest for British thrillers (I also found Ffolkes on the same roundup, but probably cannot recommend that one as strongly, except to diehard Roger Moore fans). The former film is flat-out excellent; anyone who likes thriller / action films like Die Hard will surely enjoy Juggernaut, which is about a bomb squad defusing two bombs aboard a passenger liner at sea. Juggernaut's greatest strength, besides its extremely tight and tension-filled script, is its all-star British cast, including Richard Harris, Omar Sharif, Anthony Hopkins, Ian Holm, and Julian Glover.

The appeal of The Wild Geese may be more selective, as it is a war film about an aging group of retired commandoes going on one last mission. What redeems the film is its cast -- Richard Burton, Richard Harris, Roger Moore, and Hardy Kruger -- and its focus on the relationships between the key team members. It is also quite funny at times, exploiting its principals' advancing age to show how difficult it is for them to get back into military shape etc. Ultimately a poignant male-centered buddy film, The Wild Geese is highly recommended IF you like that genre or are a particular fan of any or all of the film's stars.

L'Avventura (1960, dir. Michelangelo Antonioni) was another film I saw at the Dryden this fall, and it was simply terrific. I am relatively behind on my Italian cinema, having only just gotten serious about Fellini this past summer (more on that development in a moment), but I must say Antonioni has surely caught my attention with his gently nuanced, at times darkly comic portrayal of young Italian socialites. Like a more grittily realistic yet emotionally tender version of Fellini's La Dolce Vita, Antonioni's 1960 art-cinema classic is surely one of the finest and most memorable movies I saw this year. On to his Red Desert next!

Italian film director Federico Fellini.

On the list of Directors I knew a little about but got to know better this year are Julie Taymor, Federico Fellini, Sam Peckinpah, John Ford, and Anthony Mann. I have discussed Ford before and plan to write separate appreciations for Mann and Taymor, but I will say a few words about my great Fellini adventure and my delve deeper into Peckinpah's cinema.

I began this summer woefully lacking in direct experience of the work of Federico Fellini, having only seen 8 1/2 (1963) and brief excerpts from La Dolce Vita (1960) and Fellini Satyricon (1969). However, over the summer I increased my exposure to this wonderful and influential filmmaker via viewings of two of his masterpieces: La Dolce Vita and Amarcord (1973). Both of these are simply fantastic films. Amarcord is probably the more "accessible" of the two, being in (vibrant) color and being a bit more sentimental in tone than other Fellini films I've seen. However, for me, Vita is now my favorite Fellini film of all. More downbeat and less overtly carnivalesque than 8 1/2, Vita is a true masterpiece of 1960's European cinema that accurately captures upper-middle-class ennui even more poignantly and bitingly than the American film The Graduate would seven years later. Suffice to say, Fellini has totally won me over; next on my Fellini viewing list are La Strada (1954) and Nights of Cabiria (1957).

As far as Peckinpah goes, I was already a huge fan of his epic revisionist Western The Wild Bunch (1969); it is one of my all-time favorite films. But over the summer I caught four more of his films, winners all: the noir-ish Bring Me The Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974), the comedy/western The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970), the controversial thriller Straw Dogs (1971), and his late-career downbeat Western Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973). I confess to enjoying the former two over the latter two, mainly because Alfredo Garcia is so tightly scripted, delightfully violent, and grotesquely weird;** and because Cable Hogue is so unexpectedly tender, funny, and sentimental, especially for the usually violent and action-oriented Peckinpah. Are these still sexist, male-centered films? Yes, of course; that is what you get with Peckinpah. Yet Hogue and Garcia contain two of the best-developed women characters we're likely to get out of the misogynistic director, especially Hogue's Hildy (Stella Stevens). Also, Hogue contains one of Jason Robards' all-time best performances, rendered delightfully comic by his interactions with David Warner as a lothario/priest. Both Dogs and Pat Garrett are definitely worth seeing, though the former suffers from a contrived-feeling plot, and the latter is just so relentlessly bleak and downbeat (and this from a viewer who typically enjoys such things) that it was hard to "enjoy" in the usual sense of the word. Also, Bob Dylan's onscreen appearance in a minor yet pervasive role in Garrett is distracting.

Finally, in terms of memorable at-home viewing, I saw two really dynamite 1930s horror films this year: James Whale's The Old Dark House (1932) and Carl Theodor Dreyer's Vampyr (1932). I don't have much to say about these except: see them! House may well be Whale's greatest film, and Vampyr is one of the most creepily disturbing, and by far the most artfully and beautifully shot, vampire films I have ever seen. Only Murnau's Nosferatu is in this same league, and that just barely.

My Best Moviegoing Experiences this year were the discovery of "silent Tuesdays" at the Dryden Theater in Rochester and attending my first-ever screening at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) Lightbox Theater. I have posted about the former before; I would only like to add here that since writing that I have been to see film historian and pianist extraordinaire Phil Carli introduce and accompany the excellent, expressionistic silent film The Scarlet Letter (1926, dir. Victor Sjostrom), and the experience was EVEN BETTER than seeing and hearing him accompany The Lodger. Carli admitted that Letter is one of his personal favorite movies, and I think his enthusiasm for it came through in his piano accompaniment that night; it was even more nuanced and emotive than his Hitchcock score had been.

Bette Davis -- one of my favorite golden-age screen actresses -- in the superb

The Little Foxes.

My trip to the TIFF Lightbox -- a beautiful, multi-screen facility in downtown Toronto -- was quite thrilling as well. I was there to see Little Foxes (1941, dir. William Wyler), part of a series of Bette Davis films being screened there this fall. The movie was simply great, as were the book offerings in the TIFF Gift Shop. Not many "standard" bookstores, no matter how well-stocked, carry many of the types of books I most enjoy, i.e., works of film criticism and film history beyond the most obvious biographical works. TIFF's shop had several such books, including a fairly complete array of BFI essays on individual films. What a treat!

Also deserving of mention in the "Best Moviegoing Experiences" category this year was my trip to the Original Princess Theater in Waterloo, Ontario to see the brilliant satire Austenland (2013). The Princess is a longstanding neighborhood art-house theater in downtown Waterloo, and Austenland, starring Keri Russell and Jennifer Coolidge, is a sharp, perfectly constructed satire of Jane Austen fandom and the traditional conventions of the cinematic romantic comedy. I think many reviewers missed the point of this film, taking it for a "failed" romantic comedy. However, like Spring Breakers, Austenland requires the viewer to acknowledge its ironical stance toward its own content; like Breakers, Austenland is clearly intended as satire. Seen in that light, it is completely delightful, extraordinarily witty, and very canny about its subject matter. In short, it is one of the smartest and funniest films I saw all year.

Concluding thoughts: If I were going to recommend only three of the films discussed above to my readers (whether or not they were this year's releases), they would be 12 Years a Slave, Blackfish, and We Need to Talk About Kevin. These three movies suggest themselves mostly due to their content, not so much their formal or visual boldness. While all three are very well-made, only 12 Years contains any formal devices -- mainly a couple extraordinarily (and excruciatingly) long takes and some interesting use of sound -- that could be described as "experimental" in any way. No, I recommend these films to everyone because I think the themes and subject matter they tackle -- American slavery, our ethical responsibility to whales, and a family confronting the reality of a sociopath in its midst -- are unique and urgent. We don't often see films willing to look at subjects like these so sensitively and unflinchingly. And while there is surely a place for movies as "escapist" entertainment, as A.O. Scott has written,

what if, at least some of the time, we feel an urge to escape from escapism? For most of the past decade, magical thinking has been elevated from a diversion to an ideological principle. The benign faith that dreams will come true can be hard to distinguish from the more sinister seduction of believing in lies. To counter the tyranny of fantasy entrenched on Wall Street and in Washington as well as in Hollywood, it seems possible that engagement with the world as it is might reassert itself as an aesthetic strategy. Perhaps it would be worth considering that what we need from movies, in the face of a dismaying and confusing real world, is realism.Scott's comments were published in 2009, but resonate very strongly four years later. I hope your own movie-going year was stimulating and diverse, and here's to an equally exciting 2014!

Officer Mullins and Agent Ashburn say:

"We hope you had a fun moviegoing year!"

--

* UPDATE: Since posting this retrospective I discovered this feminist appreciation of Spring Breakers by Britt Hayes of Screencrush, in which she writes: "'Spring Breakers' is a surprisingly smart film that explores the fantasy of female agency amidst the garish dayglo excess of Spring Break [. . .] The film asks us why we want to see these girls in increasingly dangerous situations, how they could be so empowered and take agency over themselves and the men who surround them, and ultimately why we don't believe they ever could have that agency." Well said!

** Now that I have seen Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia -- probably my second favorite Peckinpah film after The Wild Bunch -- I am convinced that it has exerted a particularly strong influence upon Quentin Tarantino's early work, especially Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, and his 1996 collaboration with Robert Rodriguez, From Dusk Till Dawn.