Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde is one of three films -- the other two being The Graduate and Easy Rider -- that announced the arrival of the "Hollywood Renaissance," a unique period in Hollywood filmmaking that lasted from about 1967, the year of Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate's releases, until roughly 1980, at which time the "Blockbuster" mode of production took over the U.S. movie-making business.

The "Hollywood Renaissance" (sometimes called the "New Hollywood") was driven largely by up-and-coming Baby Boomer directors like Penn, Peter Bogdanovich, Roman Polanski, Francis Ford Coppola, Hal Ashby, Martin Scorsese, and William Friedkin. These young filmmakers, influenced by the American social upheavals of the 1960s and the cinematic innovations of the French New Wave, brought explicit sex, drugs, rock and roll, and a countercultural ethos to the American cinema throughout the decade of the 1970s. According to film historian and journalist Peter Biskind, the New Hollywood period was “the last time Hollywood produced a body of risky, high-quality work [. . .] that defied traditional narrative conventions, that challenged the tyranny of technical correctness, that broke the taboos of language and behavior, that dared to end unhappily.”*

Of course, the Hollywood Renaissance wasn't the last time any U.S. filmmakers produced risky or artistically challenging work; it's just that, after the 1970s, those risk-takers had to seek support and distribution through independent channels (hence the major boom in American independent cinema during the 1980s). What makes the Hollywood Renaissance period so unique and so interesting is that, for a brief decade, young, (mostly) counter-cultural "outsiders" took over the reins of the most powerful studio production apparatus on earth, using Hollywood's stars, technical resources, and money to collectively produce a body of work unlike anything ever made in Hollywood before or since.**

Bonnie and Clyde is a perfect representation of what made the Hollywood films of the late 1960s and 1970s so special. Witty, action-packed, and (for its time) quite violent and bloody, the picture celebrates youth on the run, a counter-cultural blast of energy in line with the youth political activism and "sex, drugs,and rock-and-roll" culture it addressed. Perhaps less subtly witty than its counterpart, The Graduate, Bonnie and Clyde nevertheless makes youthful rage and rebellion look damn sexy and damn fun. Ostensibly about two real-life 1930s gangsters, Bonnie and Clyde is really about the youth culture of the late 1960s. Its anti-authoritarian posturing, perhaps best symbolized by the sequences in which Clyde and a displaced sharecropper shoot out the windows of the latter's repossessed home, or when the Barrow gang humiliate the Texas Ranger sent to capture them, is a more accurate harbinger of the tone of the Hollywood Renaissance films to come than is the more quirky Graduate. Bonnie and Clyde's notoriously bloody finale also foreshadows the grim endings of other key films of the period, like Easy Rider, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Sam Peckinpah's elegiac anti-Western The Wild Bunch (all 1969), and Alan J. Pakula's conspiracy thriller The Parallax View (1974).

The Barrow Gang humiliates Texas Ranger Frank Hamer, evincing the film's

glamorous and self-aware anti-authoritarianism.

glamorous and self-aware anti-authoritarianism.

As Mark Harris writes, Bonnie and Clyde was almost directed by French New Wave director Francois Truffaut; screenwriters Robert Benton and David Newman approached the Frenchman several times but he ultimately turned the project down in order to direct his (pretty damn good) English-language adaptation of Fahrenheit 451 (1966).*** So Benton and Newman sent the script to Warren Beatty, who fell in love with the project and told them, "You've written a French film -- you need an American director."† It was Beatty who brought Arthur Penn in to direct Bonnie and Clyde, having worked with him before on Mickey One (1965), a film Barry Langford calls "the American film most thoroughly imbued with the stylistic lexicon of the early French New Wave."†† Throughout production on Bonnie and Clyde, Beatty and Penn had what can be best described as a fruitfully combative relationship -- they loved to argue and haggle with each other over every little creative decision, and while their on-set fighting made certain other cast and crew members uneasy, both men described their process in interviews as being a happy and productive one.

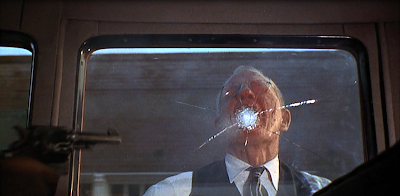

The film's most lasting contribution to film history is its startlingly effective mixture of ironic humor and graphic violence; like Sam Peckinpah's and Sergio Leone's work during this same period, Bonnie and Clyde has exerted a potent influence over future Generation X filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino and David Fincher. The film's most obviously violent sequence is its lengthy, slow-motion finale, which "includes sixty shots in less than a minute" and during which "Penn used four cameras for every setup, each one filming from the same angle but running at a different speed."††† However, the movie's most controversial single shot is the one depicted below, in which a banker is bloodily gunned down while the gun that shot him is still in the frame. We take such shots (ha, ha) for granted nowadays, but this was a risky and trendsetting choice on the part of Bonnie and Clyde's creators.

The film's most lasting contribution to film history is its startlingly effective mixture of ironic humor and graphic violence; like Sam Peckinpah's and Sergio Leone's work during this same period, Bonnie and Clyde has exerted a potent influence over future Generation X filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino and David Fincher. The film's most obviously violent sequence is its lengthy, slow-motion finale, which "includes sixty shots in less than a minute" and during which "Penn used four cameras for every setup, each one filming from the same angle but running at a different speed."††† However, the movie's most controversial single shot is the one depicted below, in which a banker is bloodily gunned down while the gun that shot him is still in the frame. We take such shots (ha, ha) for granted nowadays, but this was a risky and trendsetting choice on the part of Bonnie and Clyde's creators.

One of Bonnie and Clyde's most confrontationally violent images: Clyde shoots

the banker in the face -- with the gun in the same frame as the victim.

So, despite Entertainment Weekly's excessive propensity to lionize American films of the 1970s, I cannot disagree with their placement of Bonnie and Clyde so high on their Top 100 list. It is quite simply a must-see film that, in addition to its enormous historical significance and ongoing influence, is every bit as humorous, glamorous, and exciting now as it was when it was made.

Bonus afterthought: Once you have seen Bonnie and Clyde I strongly recommend Arthur Penn's 1975 Gene Hackman vehicle, the wonderful neo-noir Night Moves. It features Hackman at his frumpy, haggard best, attempting to solve a twisted case involving a very young Melanie Griffith in her debut screen role.

--

* Biskind, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls (Simon & Schuster, 1999) p. 17.

** Sure, there have been a few exceptions to the usual rule of Hollywood's playing things incredibly safe: for example, Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is a formally experimental and politically contentious film produced by a Hollywood studio, and von Stroheim's work also leaps to mind. But not before or since the 1970s has such carte blanche been given to a whole group of young filmmakers to basically flip the bird to the old Hollywood formulas and ideologies, which have, since the release of Jaws and Star Wars, reasserted themselves with a vengeance.

*** Harris, Pictures at a Revolution (Penguin, 2008) pp. 34-41 and 93-96.

† Harris, Pictures p. 96.

†† Langford, Post-Classical Hollywood (Edinburgh UP, 2010) pp. 92-3.

††† Harris, Pictures pp. 254-57.

Another nice one. And thanks for the Night Moves reminder--I keep forgetting to check it out.

ReplyDeleteDefinitely worth a look -- I re-watched it this past summer and it only gets better with repeat viewings!

Delete