In the past several days, I have seen two of the films mentioned at the end of my 2015 roundup as the ones I most wanted to see next. I have not been disappointed. Both Carol and Room, especially the latter, are must-sees. They are two of the most emotionally layered and holistically satisfying movies I have seen this winter.

Carol is the latest film from New Queer Cinema auteur Todd Haynes, who I recently described in a Facebook post as being "the Stanley Kubrick of queer cinema." I call him this due to his meticulous attention to detail and the tendency of his films to unfold at what I call a "stately" pace. Not slow exactly, but deliberate and visually dense, much like Kubrick's films tend to be.*

Carol is adapted from a Patricia Highsmith novel called The Price of Salt (1952). Both film and novel are about a budding homoerotic romance between a shopgirl (Rooney Mara) and an older woman (Cate Blanchett) who is in the process of divorcing her estranged husband (Kyle Chandler) while maintaining connections with her beloved young daughter Rindy (Sadie and Kk Heim). What is most remarkable to me about Carol -- besides its amazingly high quality of cinematic craft and eye-popping set and costume design -- is its attention to the fine nuance of human interactions, applied to ALL the relationships in the movie. That is, while the film's primary focus is upon the romance between Therese and Carol, it really shows us how that new, fragile relationship unfolds within a matrix of other key interrelationships, especially Carol's lingering tie to her soon-to-be-ex-husband Harge and her deep bond with ex-lover and current best friend Abby (played brilliantly by a superb Sarah Paulson).

Rooney Mara gives the standout performance in Carol as shy shopgirl Therese. Despite its title, Carol mainly unfolds from aspiring photographer Therese's point of view.

Most importantly, Carol treats all of these characters and interrelationships with nuance and respect, refusing to lionize or vilify any one person at the expense of another. Sure, many of the men in the story, especially one of Therese's young male suitors and Harge himself, make presumptions about their entitlement to, even implicit ownership of, their female objects of desire. Yet the film does not paint them as irredeemable villains -- Harge in particular is able to do the right thing by the end of the film, even though he is still an unthinkingly patriarchal dickhead. As in Haynes' earlier works Safe (1995) and Far From Heaven (2002), Carol manages to critique patriarchy and show us its general savagery without utterly dehumanizing its onscreen male agents.

Carol conveys all the fine details of its characters' feelings toward each other via delicate, precise attention to character gesture, camera distance, and editing. One of my favorite examples of this is a close-up of a small hand gesture Carol makes at the beginning and end of the film (we see the same sequence twice, as a kind of frame story). It is a silent placement of her hand on Therese's shoulder that has enormous emotional consequences, yet it is not over-emphasized with a clumsy music cue nor unduly broadcast by the camera pushing in or by an obvious reaction shot. No, it just happens, we see it, and if we have been paying attention then we know what great emotional weight it carries. This is confident, assured filmmaking that trusts its audience to make connections.

In other words, Carol is a film every thinking filmgoer should see. A little looser and more upbeat than some of Haynes' previous works, and endowed with the world-class period set design, amazing costumes, and beautifully composed visuals we have come to expect from this directorial master, Carol explores the nuances of adult relationships in a way that few American films do. Highly recommended.

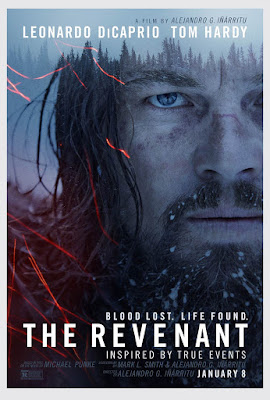

Even more highly recommended is Room, director Lenny Abrahamson's follow-up to 2014's remarkable Frank. If Carol easily beats out the visually stunning yet emotionally hollow The Revenant for overall impact, then Room in turn beats out Carol -- or pretty much anything else I've seen recently -- in that area. Resonant, heartfelt, and intermittently heartbreaking without being exploitative or nearly as harrowing as I expected, Room is an absolute must-see.

One probably wouldn't anticipate Room's accessibility and potentially wide appeal given its bleak-sounding premise: a mother (Brie Larson), kidnapped and held in sexual servitude for seven years, has a child, Jack (Jacob Tremblay), two years into her stint as a prisoner in a windowless (but skylight-equipped) shed. That is all backstory; the film depicts the weeks following Jack's fifth birthday, including the duo's nail-biting escape from captivity and -- really the bulk of the movie -- how they begin to adjust to life in the outside world.

Regular readers know that I like bleak, grim films, and I fully expected Room to be pretty damn dark. Yet it mostly isn't -- that is its miracle. Room is, in fact, an enormously uplifting, even feel-goodish film about how these two central characters survive their imprisonment and beyond by "sharing their strong." It is about human bonds, parental love, and the will to survive. Its escape sequence is one of the best suspense sequences I have seen in a long time, and its performances, especially those given by Larson, Tremblay, and Joan Allen, are also some of the best I've seen this season.**

Room deploys a lot of handheld camera and, especially in its opening thirty minutes in the confines of the shed, lots of close-ups. This technique really works. Even once the mother and son reach the outside, the film is very sparing in its use of wide shots -- the focus remains, via abundant close-up work, tightly on these two, their feelings, and their bond. As such, Room is one of the most beautiful paeans to motherhood I have ever seen -- it rivals classic maternal melodramas like Stella Dallas (1937) and Terms of Endearment (1983), and contemporary works like We Need to Talk about Kevin (2011), in this regard. Room is, quite simply, an emotionally rich movie that all moviegoers interested in these themes should see.

The film's point of view -- carried over from the novel by Emma Donoghue, who also adapted the screenplay -- is Jack's. I think this is what allows the film to work so well, and permits Abrahamson and company to depict the opening scenes in the shed without ever becoming graphic or exploitative about the horrible things occurring there. No, we are aware -- in ways Jack himself is not -- of what the mother is going through, yet the emphasis remains on the mother-son dyad, their love, their mundane ways of getting through the days, and their eventual planning for their escape.

In its fixation on the emotional, rather than legal or procedural, consequences of the mother's kidnapping, long-term imprisonment, and sexual assault, Room offers an implicit critique of films that use female suffering as a pretense for masculine action, legal resolution, and/or tales of violent vengeance. Room dares to be something much more provocative and vulnerable: it is a film about love, and about human strength and weakness, told from the point of view of a child who has been raised under unique and (somewhat unbeknownst to him) traumatic circumstances. It is a beautifully crafted film about dark deeds that nevertheless ultimately functions as a meditation about love and endurance and family ties.

Both Carol and Room are films about younger protagonists (Therese, Jack) who explore new horizons (lesbianism, the outside world). Haynes' film is perhaps formally more beautiful -- the hair! the costumes! the gorgeously framed shots through car windows! -- yet Room delivers emotionally in a way few films do. Confident, bold, true, and resonant, Room is one of the great films of its period. You should go see it.

Room director Lenny Abrahamson with most of his film's stellar cast plus Room novelist / screenwriter Emma Donoghue.

* Of course there are exceptions to the stateliness of Kubrick and Haynes. Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove (1964) and A Clockwork Orange (1971) move along at headlong, even frantic paces, and Haynes' three-part debut film Poison (1991) and his glam rock homage Velvet Goldmine (1998) both exhibit a certain pep and fierce energy that his other films, like Safe (1995), Far From Heaven (2002), and Carol eschew.

** If I were able to regard the Academy Awards as an indicator of quality, I would hope for Brie Larson to win the best actress Oscar this February. I would also want to give Rooney Mara an award for her work in Carol -- she outshines Cate Blanchett IMO -- and young master Tremblay for his knockout turn as Jack in Room.