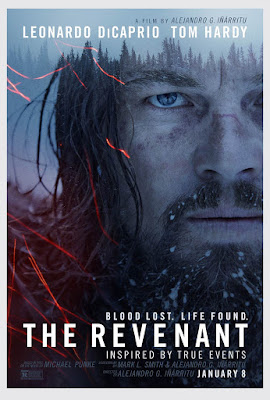

I would be tempted to call The Revenant a noble failure except that it doesn't truly fail at anything its sets out to do -- I don't think. However, this uncertainty on my part is the root of my problem with the movie.

The Revenant's single biggest weakness is the arc of its "betrayal and revenge" story, which is incredibly predictable and conventional in the way it plays out. There are no surprises nor cathartic revelations to be had here. Now of course I have no inherent problem with films that stick to a formula, but The Revenant seems to want to suggest something more than a simple genre exercise via its slow pacing and arresting camera work. Yet its "arty," seemingly thematically suggestive visual aesthetic does not quite jibe with the simple, straightforward story the film actually tells. I do not know what, if anything, some of The Revenant's visuals, specifically its lingering shots of nature imagery and heavy-handed flashback sequences, are attempting to convey on a deeper level.

Maybe I expected too much from the film narratively and thematically. If indeed my initial expectations for The Revenant were unrealistically high, then the director and film have no one to blame but themselves. I have written elsewhere about how great I think Birdman is -- it is basically one of my top two or three films of 2014. Birdman more or less perfectly balances its straightforward comedy elements with its thematic deconstruction of the U.S. entertainment industry -- its visual aesthetic, its narrative structure, and its underlying thematic meaning fit perfectly together. It totally earns its productively ambiguous conclusion. (In contrast, The Revenant's final shot suggests an intertextual shout-out to the last shot of Birdman more so than anything intrinsically meaningful to The Revenant.)

Furthermore, the stories of The Revenant's grueling, troubled production, and Inarritu's and the cast and crews' perseverance in the face of those obstacles, have lent the whole thing an aura of momentousness and the promise of substantial artistic achievement. I admire Inarritu and appreciate his commitment to location shooting and his perfectionist tendencies in the camera and lighting departments. Yet if Inarritu and company struggled so hard to get this film in the can, wouldn't we hope it would be a total masterwork?

Yes we would, but the film, for all its great achievements, has problems:

1. Let's return to the Malick - Herzog comparison. Malick -- I am thinking mainly of The Tree of Life (2011) here, though all his films (that I've seen) evince this tendency* -- uses natural imagery to suggest deep interior states of character psychology and, simultaneously, something cosmic and vast and non-human at the same time. That is, there is an ambiguous yet meaningful symbolic aspect to Malick's use of such imagery. For example, The Tree of Life's "through the eons" sequence and concluding oceanside scenes, and the moving desert landscape shots paired with Holly's voice-overs in Badlands (1973), meld natural landscapes with character emotions and states of mind, using imagery to create a kind of landscape of the human soul.

Conversely, as Herzog says on camera in Les Blank's great documentary Burden of Dreams (1982),

Nature here is violent, base. Of course there is a lot of misery, but it is the same misery that is all around us. The trees here are in misery, and the birds are in misery -- I don't think they sing, they just screech in pain.For Herzog, nature is a brutal, existential place, not necessarily an abstract symbol for other things as it might be in Malick or in Nicholas Winding Refn's Valhalla Rising (2009). Nature is just nature and in Herzog's view it simply wants to kill us and/or make us miserable. Thus when Herzog's camera lingers on the onrushing river early in Aguirre, Wrath of God (1972) it is meant to suggest that that river is a physically insurmountable thing -- indeed, it will prove to be a key factor in Aguirre's undoing. Though the shot is lengthy and therefore somewhat meditative, I don't think it is meant to suggest any abstract meaning to the river -- no, Aguirre presents that river as simply an indefatigable obstacle to be struggled with, not as a metaphor for any character's inner state. This point of view is consistent with the rest of the film and with the director's larger body of work.

For me, the main problem with The Revenant is that I cannot tell if its meditative, drawn-out nature shots are meant to depict the beautiful but brutal indifference of the wilderness, or to work as some kind of metaphorical cypher giving us access to Glass's soul. I don't think the film knows either. The best clue we have is that The Revenant is very much situated within the subjectivity of Glass -- in the opening shot we literally inhabit his point of view, and throughout the movie we get several weird flashbacks and visions and quasi-dream sequences shown from his perspective. These sequences are supposed to tell us about Glass's interior state but really only repeatedly and unnecessarily reinforce the idea that he loves his wife and son, neither of whom we are allowed to know in depth or care about. Is his love for his indigenous family members really all that motivates this man? Is that all that's going on here?

As EW's Chris Nashawaty writes, The Revenant "almost works better as a series of stunning images and surreal sequences than as an emotionally satisfying story." He concludes that

Here, story and style never quite get on the same page. It’s a movie that’s so focused on dazzling your eyes that it never quite finds its way into your heart.I am sadly inclined to agree.

2. Whatever steps The Revenant takes to humanize its indigenous characters -- and I count only one, a speech given by Hikuc (Arthur RedCloud) to the French traders -- those efforts come too little, too late. For the movie's striking, impactful, pulse-pounding opening sequence places the viewer among the white traders and frames the attacking Arikara as terrifying, sinister monsters of whom we should be afraid. We see their death-dealing arrows long before we see them, and none of the natives are given individual identities we might empathize with or relate to.

I am sure the filmmakers do not consciously intend to recycle damaging indigenous stereotypes, as DiCaprio's conclusion to his Golden Globes acceptance speech makes clear. Yet as Aisha Harris notes,

What makes this [speech] so awkward and cynical is the fact that it’s so at odds with the movie DiCaprio and director Alejandro González Iñárritu produced. The Revenant is only the latest in a long history of major Hollywood studio films featuring indigenous characters that is told from the white male perspective.This is hard to argue with. I am sure DiCaprio and Inarritu mean well, but they have indeed made a film whose racial politics and white-male-centeredness are as retrograde as a 1940s Western. As Carole Cadwalladr puts it in her scathing Guardian op-ed piece, The Revenant is a "vacuous revenge tale that is simply pain as spectacle. [. . .] It's simply the kind of tedious, emotionally vacant film that has certain critics and Academy Award judges wetting their pants." Harsh but not entirely inaccurate words.

3. As the AV Club's Iggy Vishnevetsky points out, there are a great many actors who could have assayed the role of Hugh Glass with more depth and interest than Leonardo DiCaprio does -- his cast-mate Tom Hardy chief among them. Indeed, I found as the film unfolded that DiCaprio, while certainly very capable and believable, did not really wow me -- I kept getting distracted by the supporting players like Hardy, Will Poulter, Domnhall Gleeson, and the bear.**

The bear sez: "I just want to thank my co-star Leonard, and of course my director Alejandro. I'm a two-year-old bear from the Sierra mountains, you know, and you took a chance on me, and honestly, I don't forget it, pal."

To be clear, I really enjoyed The Revenant. I will probably watch it again, if for no other reason that I want another look at its stellar camera work, lighting, and mise-en-scene. My criticisms here are meant to finely point out how this film manages not to be an utter masterpiece in my view. It is still better than 98% of all other movies out there and most everyone should go see it, in a theater if at all possible.

In the end, I wanted to like The Revenant more than I did. I wanted it to be an outright masterpiece. Instead it is a visual stunner with great individual performances but with an extremely questionable ideological point of view and a few inconsistencies that keep it from cohering as powerfully as perhaps it could. It is too thin on the ground thematically given its running time (two and a half hours) and visual grandeur. It suggests -- too vaguely and indeterminately -- more than it ultimately delivers.***

UPDATE 2/26/2016: I thought last year's Birdman was flat-out superb and I do not agree with this author's hyperbolic assertion that Alfonso Cuaron is "a genius," but I generally agree with his assessment of Inarritu's latest effort:

Even the best thing about The Revenant is maddening: It is one of the most visually stunning studio films in recent memory, with long takes winding through dusk-dappled woods, seemingly impossible shots of men floating through whitewater rapids and horses falling off cliffs. All this useless beauty, in service of obscuring a lazy screenplay and aggressively dimensionless characters.Ouch! Sad but true.

UPDATE 5/21/2016: For an even more in-depth analysis of Innaritu's self-defeating overuse of a "BEAUTIFUL & SOULFUL" visual aesthetic, see Film Crit Hulk's long discussion of The Revenant and Mad Max: Fury Road (which includes discussion of Malick).

--

* I really need to see The New World (2005), one of the few Malick films I haven't seen, since I suspect it may be the best one to compare to The Revenant to illustrate how Inarritu's use of "trippy / meditative nature visuals" differs from Malick's.

** You may think I'm joking but I'm serious: the bear attack is the best scene in the film by far, an amazingly believable and pulse-pounding sequence the likes of which I have never seen before.

*** In this one way only The Revenant reminds me of Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight (2008), another film that seems at first glance to have a lot on its mind, but finally reveals itself to be a straightforward white male power fantasy and a retrograde celebration of post-9/11 neoconservative values.

No comments:

Post a Comment